WEEK 4

AGENCY THEORY ~

(supplemental Altruism)

Agency theory is a principle that is used to explain and resolve issues in the relationship between business principals and their agents. Most commonly, that relationship is the one between shareholders, as principals, and company executives, as agents.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Agency theory attempts to explain and resolve disputes over the respective priorities between principals and their agents.

Principals rely on agents to execute certain transactions, which results in a difference in agreement on priorities and methods.

The difference in priorities and interests between agents and principals is known as the principal-agent problem.

Resolving the differences in expectations is called "reducing agency loss."

Performance-based compensation (incentive) is one way that is used to achieve a balance between principal and agent.

Common principal-agent relationships include shareholders and management, financial planners and their clients, and lessees and lessors.

Managing Social and Human Capital

People are the most valuable asset of any business, but they are also the most unpredictable, and the most difficult asset to manage. And although managing people well is critical to the health of any organization, most managers don't get the training they need to make good management decisions. Now, award-winning authors and renowned management Professors Mike Useem and Peter Cappelli of the Wharton School have designed this course to introduce you to the key elements of managing people. Based on their popular course at Wharton, this course will teach you how to motivate individual performance and design reward systems, how to design jobs and organize work for high performance, how to make good and timely management decisions, and how to design and change your organization’s architecture. By the end of this course, you'll have developed the skills you need to start motivating, organizing, and rewarding people in your organization so that you can thrive as a business and as a social organization.

Asymmetric information, also known as "information failure," occurs when one party to an economic transaction possesses greater material knowledge than the other party.

The Not-So-Orderly Withdrawal

Even during the worst days of the United States’ evacuation from Afghanistan, with images of Afghans falling from the wings of U.S. military transport planes and crowds at Hamid Karzai International Airport piling up on social media, the Biden administration stuck to the script. The administration staunchly defended the evacuation of 125,000 people, with U.S. President Joe Biden calling the effort historic and shunting aside naysayers who said the White House should have ramped up evacuations sooner.

But that narrative faced scrutiny on Capitol Hill in the weeks after U.S. troops left in August 2021, as lawmakers scrambled to get hundreds of stranded U.S. citizens and thousands of legal permanent residents out of the country. Now, it’s on the verge of falling apart after an internal U.S. Army report uncovered by the Washington Post revealed—from the perspective of the troops whose boots were on the ground—just how messy the two-week evacuation actually was.

For months, officials said, the U.S. Embassy in Kabul stonewalled military commanders about planning for an evacuation, with acting U.S. Afghanistan envoy Ross Wilson reluctant to surrender influence on the ground. Even as Marines landed at the airport in late July 2021 to assist with planning, it was not until Aug. 11, 2021, just five days before the Taliban took over Kabul and then-Afghan President Ashraf Ghani fled the country, that diplomats on the ground got serious about getting out.

“We had ad hoc meetings with the embassy, but they didn’t want to talk about the [evacuation],” a military officer whose name was redacted told Army investigators. “They really didn’t want to talk about it. … It was a stonewall for not really being able to plan. We essentially planned the [evacuation] with [the U.S. State Department] and partner input in about five days.”

Even though top military officials—such as retired Gen. Austin “Scott” Miller, then the top U.S. commander in Afghanistan—were expressing concerns about the Taliban’s lightning march through the country as early as May 2021, the embassy did little to scale down its facility, then the largest embassy in the world with 4,000 employees. “Trying to get the embassy to discuss the [evacuation] was like pulling teeth until early August,” added Marine Corps Brig. Gen. Farrell J. Sullivan, who commanded Marines on the ground in Kabul.

In the interim, military commanders on the ground—who were already losing visibility throughout the country as the United States reduced its force to just 650 troops in the days before leaving—could only collaborate with the British on evacuation planning. Another military commander said Wilson, the top U.S. diplomat in Afghanistan, went on vacation for two weeks in the United States after accompanying Ghani to his White House meeting with Biden in June, bringing planning to a grinding halt.

“There were as many as 10 districts falling every day, getting closer and closer to Kabul,” a military officer whose name was redacted told investigators. “The embassy needed to position for withdrawal, and the ambassador didn’t get it.”

Once the evacuation began, the U.S. State Department’s prioritization for who to evacuate was fuzzy and continued to change over the two-week drawdown, military officials told investigators. “Then special interest groups overwhelmed the process,” Rear Adm. Peter Vasely, who served as the top U.S. commander for the forward-based U.S. mission in the final days, told investigators.

And the troops manning the gates were overwhelmed by requests from the administration to get VIPs into the airport. Sullivan, the Marine commander on the ground, “was receiving calls from the White House, and a lot of the requests were not [American citizens],” he said. The Washington Post reported on Thursday that requests from Pope Francis and First Lady Jill Biden were among those taxing the bandwidth of military commanders on the ground.

Worse yet, there was no plan to coordinate with the Afghan army to defend the airfield. The assumption was that the Taliban would stop outside of Kabul, and Wilson, the U.S. envoy, made a “conscious decision” not to let Afghan forces or the government know that the United States was planning for an evacuation. Biden’s decision to move the deadline for withdrawals from mid-September to the end of August also caught troops off guard, who thought they had more time to plan.

And, unfortunately for the White House, it’s a story that’s getting played out in email chains among congressional staffers overseeing probes into the final chapter of the U.S. war in Afghanistan, with a potential Republican takeover of the House of Representatives (if not also the Senate) looming in November.

The Senate is also keeping Afghanistan at the top of its agenda. On Wednesday, Sens. Chris Murphy and Todd Young convened a hearing on the future of U.S. engagement in Afghanistan and the massive humanitarian crisis wracking the country since the chaotic U.S. withdrawal. The hearing reflected the fierce debates within the U.S. government about how to offer lifelines to the Afghan people without solidifying the Taliban’s power.

“There is no good choice here,” Murphy said during the hearing. “On one hand, we cannot unduly empower the Taliban. We have to recognize the moral hazard. But on the other hand, with families that we stood with for two decades facing destitution and starvation, the solution cannot be to stand by and do nothing.”

BEFORE WE GO ANY FURTHER HERE

Below is a list of curriculum infrastructure topics that apply to our class - check the one that you feel needs addressing and comment below

37.43 USD−1.34 (3.45%) 2/10

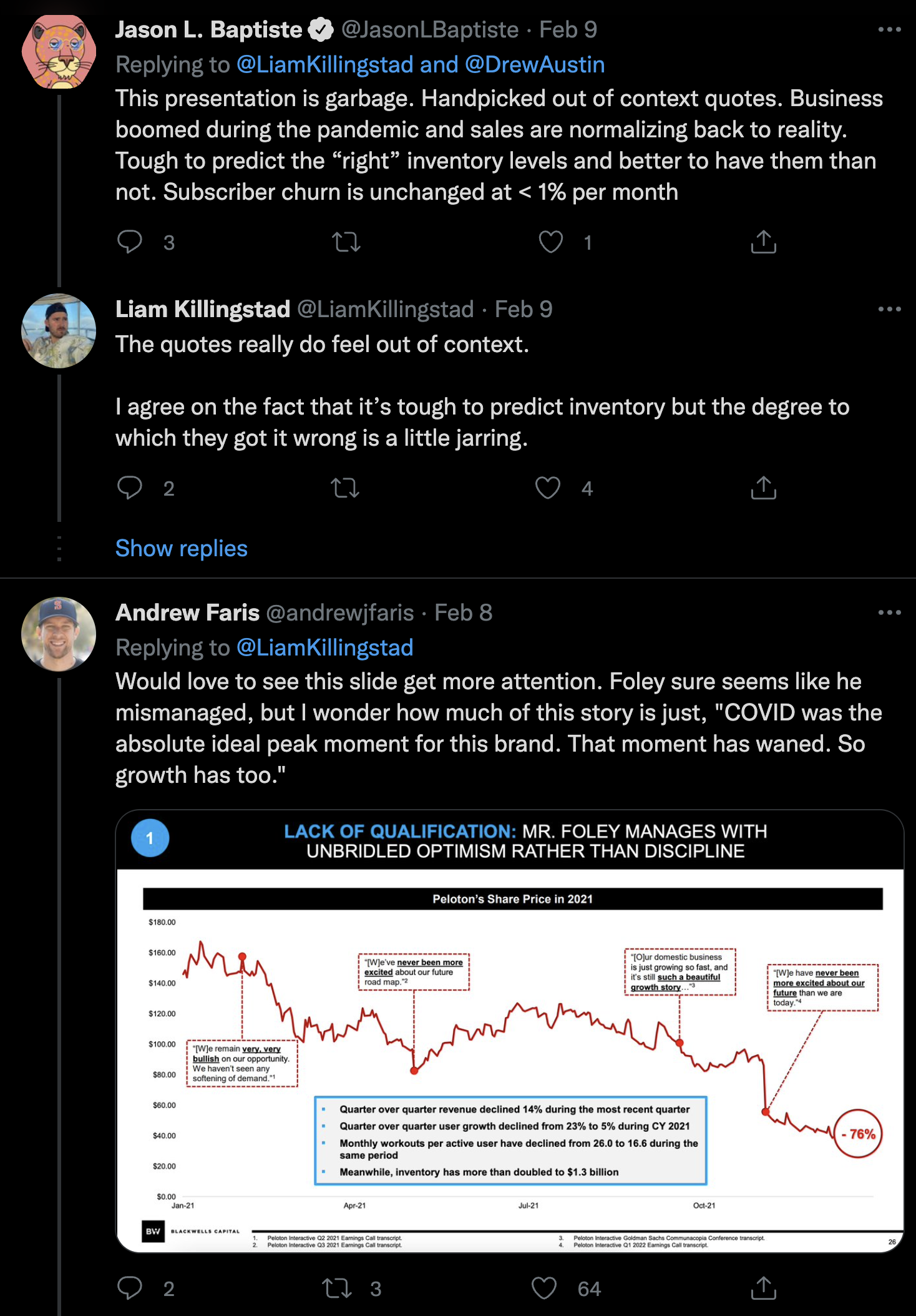

Source of capital affecting change through asymmetric information and transparency for good and/or bad

ASSIGNMENT - Phase 1

READING ASSIGNMENT II: WEEK 4

AGENCY THEORY: AN ASSESSMENT AND REVIEW {READ THIS}

Illustrate the Agent/Principal relationship in your proposed entrepreneurial venture

Again, we encounter an abundantly illustrative, yet woefully outdated application of a concept pre-2020 as it applies to a business setting where authenticity and altruism are integral parts - discuss how Agency Theory now applies (government/industry, COVID era-specific examples, et al)

Describe how Agency Theory works outside of an economic model (relationships where financial benefit are not the end goal)

How does the combination of altruism and agency theory form a symbiotic relationship and lay the foundation for social change. Is this the best place for social entrepreneurship to germinate from? Give me a single statement supporting or refuting this.

I've cited two films that colorfully illustrate Agency Theory (The Defiant Ones and Raiders of the Lost Ark). What is another example from cinema and/or literature that comes to mind for you? You’’ be asked to explain in detail where the storyline supports this exercise (i.e. "give me the idol - throw me the whip").

What is the best case Agency/Principal scenario?